I’m going to be honest: I hated Good Night, Irene by Luis Alberto Urrea. If you want to read a positive or balanced review of it, you’ll have to find that elsewhere.

What’s it about?

Based on the experiences of the author’s mother’s real service as a ‘Donut Dolly’ during World War II, Good Night, Irene follows two women who leave home to join a little-known unit of the Red Cross. Tasked with raising morale in the troops, Irene and Dorothy drive their clubmobile Rapid City from the front lines to the officers clubs to smile and flirt with the men while serving donuts and coffee.

Why didn’t I like it?

Long story short, it’s boring and doesn’t have much of a plot.

I’m not typically a tough reviewer. I’m not stingy with four- and five-star reviews, and I always feel genuinely bad when I give something a low rating, particularly when a lot of people seem to love it. Did I miss something? At least some of my complaints are matters of taste. Historical fiction is absolutely not one of my go-to genres, and I’ve read enough WWII fiction in the last few months that I’m fairly over it. That being said, I do think that most of my critiques are legitimate and that I’m not being overly, overly mean.

Or maybe I am. Very close to the start of the novel, Irene plays a game of Solitaire and there’s some narration about the joker cards. The game of Solitaire does not use jokers. I’m usually the last person on earth to catch that sort of error, and that near immediate mistake didn’t exactly prime me to be optimistic (or charitable).

I don’t want to be unrepentantly negative, so I will say this: Urrea dedicated this novel to his mother Phyllis, who was a real-life Donut Dolly. Phyllis and her real-life clubmobile companions—including Jill, whom Urrea interviewed extensively for this project—make repeated cameos. This is very cute, and in these moments I could feel the love and respect Urrea has for her.

That doesn’t make up for the book’s many, many other flaws, though. First and foremost, as I said above, is how boring it is. I read this for book club, and while I was the only one who hated the book, I was not the only one who found it painfully slow, particularly at the beginning. Most of the others in the group felt that it picked up about halfway/two-thirds of the way through; for me it absolutely did not, but even so… the halfway point is far, far too late for the book to draw attention. I famously refuse to DNF books, but I was sorely tempted. If I’m falling asleep every few pages, don’t care about there characters, and have found no plot to speak of, what exactly am I reading to the end for? I only finished for book club, but it took me so long to get through it that I truly thought this was going to be literally the first time in my life that I didn’t finish a book club pick. I did, but barely. There is nothing propulsive about Good Night, Irene, no ‘what happens next?’ The few questions I did have never got addressed, and I wasn’t alone in feeling that the book simply lacks plot. It reads more as a collection of disconnected scenes from the war than as a cohesive narrative.

I truly think that this would have been better if Urrea hadn’t written a novel and had instead helped Jill shape her memories into a collection of essays. True stories, especially if written as a collection of anecdotes, don’t all have to build on each other the same way a novel does. In its current form, Good Night, Irene has a lot of scenes that don’t serve any clear purpose. Why, for instance, do Dorothy and Irene choose to put on cringey fake French accents for an afternoon? Generously I could say they’re trying to break the monotony or that the pressure of the war is breaking them, but I’m not truly convinced there’s evidence in the text to support it. Lots of scenes seem constructed to carry a single joke, most of which weren’t actually funny to me.

It doesn’t help that I couldn’t care less about either of the women. Some of my book club companions did like them, but for my money they’re both just empty stereotypes. Irene is a girly girl and Dorothy is a tomboy. Irene had a physically abusive fiancé and Dorothy’s brother died in the war, which is what drove them to serve. Beyond that, there’s very little to them. Worse, they very much give off men-writing-women energy. Physical descriptions are squeezed in early, at very weird times, and neither woman is at all bothered by the gross behavior they receive at the hands of the GIs.

Did Urrea not realize that even the most patriotic woman might occasionally, at least once, tire of the pawing and the flirting and the pet names? Every once in a while one of them will say “don’t call me Dolly” but it’s played like an inside joke (and the girls don’t seem to have any problem being called “doll”).

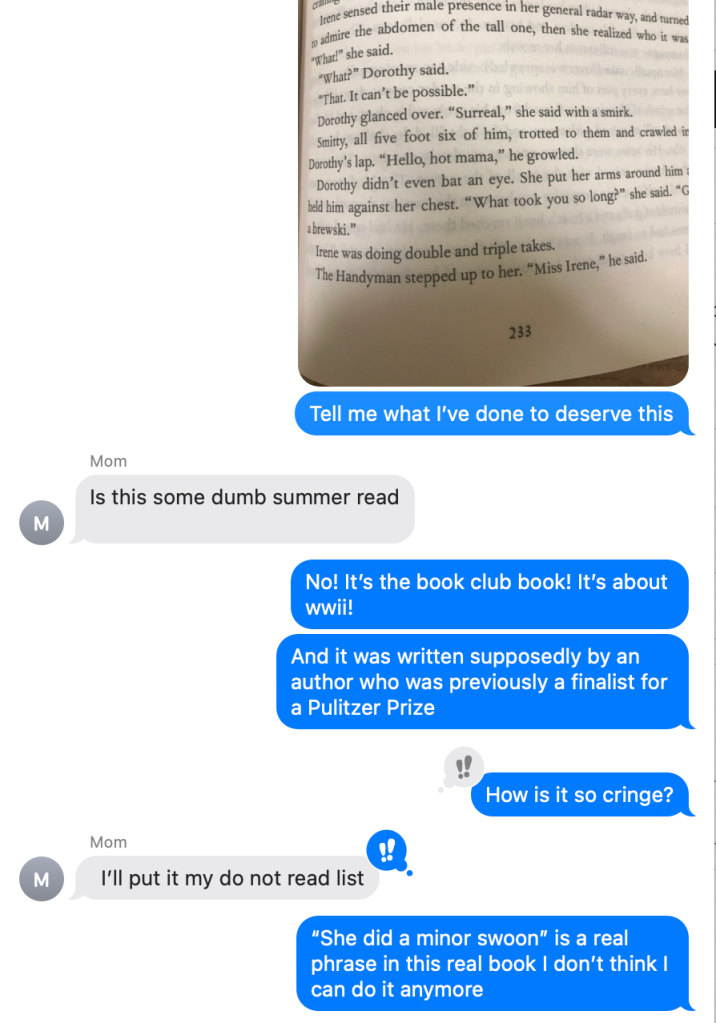

There are even moments that sound less like they were written by a human man and more like they were written by an alien educated by a man who had never met a woman before: in one scene Irene “sensed their male presence in her general radar way, and turned to admire the abdomen of the tall one” and a few sentences later Dorothy’s boyfriend “trotted to them and crawled in Dorothy’s lap. ‘Hello, hot mama,’ he growled.” I cringed very hard. In fact, I texted my mom in I’m about to quit this book despair.

Luis Alberto Urrea is a bestselling author who has won writing awards! How? He wrote the phrase “She did a minor swoon.” How am I supposed to take any of it seriously?

Even if I hadn’t seen the name on the cover of this book, there is no universe in which I could believe Good Night, Irene was written by a woman. It’s maybe not the overexaggeratedly sexed-up writing that is so maligned online, but there is something distinctly masculine about the lack of understanding about how women occupy the world, not just in the minor moments (Urrea apparently thinks that merely brushing curly hair can make it straight) but in the major ones as well. You’re telling me that Irene was repeatedly beaten by her fiancé and it’s just the inciting incident? After Irene joins the Red Cross her past abuse is never brought up again except in passing to explain why she’s there. Aside from prompting her to leave, being beaten evidently did not change Irene at all. Neither she nor Dorothy ever feels any discomfort about being constantly surrounded by armed men who haven’t seen a woman in weeks or months and who they are being asked to flirt with constantly. I’m sorry, but that would be terrifying. They receive letters that say things like I saw you for one minute six months ago and still fantasize about you or you probably don’t remember me but you gave me a donut once and I’d like to marry you after the war and they’re charmed by it. There’s not even a passing thought about this. Irene and Dorothy walk through the world—and the war—with a confidence that they’ll be untouched that is absolutely incomprehensible.

That goes double for the actual war stuff. The stated purpose of this book is to bring awareness to this under-appreciated and little-known group of war heroes, but in actuality I don’t think the Donut Dollies come across as particularly heroic here. In theory, I understand how their presence would boost morale, but Good Night, Irene makes them come across as frivolous and pampered. We’re told that they go to the front lines, but the one time they actually do experience the horrors of war upfront they’re sent overseas for an all-expenses paid beach vacation (and their boyfriends are free to just drop by). We’re told they’re sent to boost morale for the suffering GIs, but after seeing the GIs being released from a concentration camp, Patton himself apologizes to them and says he never should have sent them to see those men. When their clubmobile is shot, Irene and Dorothy’s instinctive first response is not to be afraid. It’s to be offended. They pretty much feel that they’re invincible, and why not? They’re immediately promoted to officers so that they’re treated more nicely. They apparently have an inexhaustible source of coffee and donuts, and seem to get the red carpet rolled out at every hotel stop. You wouldn’t know there was a such thing as food shortages or rationing to read this book, because the women at least are always being treated to expensive alcohol.

It just feels disingenuous to say you’re writing about women’s heroism in war and then to actually write about how the women got to go on sexy vacations, get pampered with gifts of chocolate and champagne, and prove their heroism by (spoiler) adopting a baby.

It’s not a sexist book, but it certainly doesn’t feel nearly as empowering as I expected it to, or as I assume Urrea meant it to. And just don’t get me started on the cheesy death fakeouts or the fact that the love interest is unironically called “The Handyman.”

What’s the verdict?

If you liked this book, more power to you. I barely made it through. I literally fell asleep on it more than one time (and not reading late at night; I didn’t do that with this book, because I’d rather just go to sleep intentionally) and truly thought it was going going to break my decade-long no-DNFs streak. Generally speaking, I think books should have plots, and if they don’t they definitely need to have at least one compelling character with some sort of development. Good Night, Irene does not. The best I can say about it is that I now know about the Donut Dollies, which I didn’t before, and Urrea dedicated this to his mother and her WWII heroism and that’s cute. Beyond that… Good Night, Irene is—at least for me—absolutely without anything to recommend it.

What’s next?

As far as WWII fiction goes, I highly recommend The Book Thief by Markus Zusak and The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Borrows. The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah and All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr are also good. It’s not fiction, but The Monuments Men by Robert Edsel and Bret Witter may also be a good choice. I haven’t read it, but one of my fellow book clubbers enthusiastically recommended it.

For historical fiction with compelling female characters, try The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett, Last Night at the Telegraph Club by Malinda Lo, A Clash of Steel by CB Lee, Hour of the Witch by Chris Bohjalian, The Other Boleyn Girl by Philippa Gregory, The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid, Kindred by Octavia Butler, Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce, or Burn by Patrick Ness. You’ll notice that not all those writers are women. Sure, women have a leg-up writing female characters, but that doesn’t mean no one else can do it well. Luis Alberto Urrea just didn’t with Good Night, Irene.

And finally a recommendation that has nothing to do specifically with Good Night, Irene but which deserves a shout-out anyway: The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orzcy, published in 1903, is often considered a predecessor to the masked superhero stories we know so well nowadays. It takes place during the Reign of Terror and tells the story of an enigmatic hero smuggling French aristocrats to safety, the agent determined to stop him, and a woman caught in the middle with an impossible choice in front of her. It’s wonderful, and doesn’t get read enough. If schools taught The Scarlet Pimpernel, more kids would grow up loving classic literature.

I usually love to read, but occasionally I’ll come across a book that, for me, doesn’t work on any level and it takes me a whole week to read 200 pages. The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead is one such book. I’m stringently opposed to DNFing, but if this weren’t for a book club, I would have been sorely tempted to toss it and not look back. Historical fiction isn’t my go-to genre, but I’ve heard a lot of good things about the Pulitzer-Prize-winning Whitehead and I very much expected to be impressed by his writing.

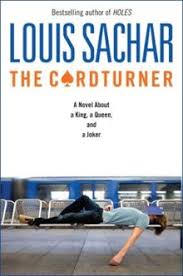

I usually love to read, but occasionally I’ll come across a book that, for me, doesn’t work on any level and it takes me a whole week to read 200 pages. The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead is one such book. I’m stringently opposed to DNFing, but if this weren’t for a book club, I would have been sorely tempted to toss it and not look back. Historical fiction isn’t my go-to genre, but I’ve heard a lot of good things about the Pulitzer-Prize-winning Whitehead and I very much expected to be impressed by his writing. I love Louis Sachar. Holes is one of my all-time favorite novels, and I can remember reading the Wayside School books over and over again when I was younger; they are honestly some of the most hilarious stories I’ve ever read. The Cardturner was published in 2010, and I’d never heard of it until I stumbled upon it at the library this year (2019). I was really excited and a little confused, because it didn’t seem possible that I could be completely unaware of a novel by a popular, bestselling author who is also one of my personal favorites. I hate to say it, but there’s a reason The Cardturner has stayed mostly under the radar.

I love Louis Sachar. Holes is one of my all-time favorite novels, and I can remember reading the Wayside School books over and over again when I was younger; they are honestly some of the most hilarious stories I’ve ever read. The Cardturner was published in 2010, and I’d never heard of it until I stumbled upon it at the library this year (2019). I was really excited and a little confused, because it didn’t seem possible that I could be completely unaware of a novel by a popular, bestselling author who is also one of my personal favorites. I hate to say it, but there’s a reason The Cardturner has stayed mostly under the radar. I have very, very slowly been making my way down one of those 100 Books to Read Before You Die lists. I didn’t actually bring my list to the library with me, which was a critical mistake. There are two classic novels with nearly identical titles. There’s On the Road by Jack Kerouac and there’s The Road by Cormac McCarthy. I picked up the latter; the novel listed is the former. In other words, I just spent two weeks reading what is very possibly the most boring, pointless book of all time and I don’t even get to cross it off my list.

I have very, very slowly been making my way down one of those 100 Books to Read Before You Die lists. I didn’t actually bring my list to the library with me, which was a critical mistake. There are two classic novels with nearly identical titles. There’s On the Road by Jack Kerouac and there’s The Road by Cormac McCarthy. I picked up the latter; the novel listed is the former. In other words, I just spent two weeks reading what is very possibly the most boring, pointless book of all time and I don’t even get to cross it off my list. I have read a lot of glowing reviews of All the Bright Places by Jennifer Niven, so I read it without even glancing at the blurb, figuring that that many people couldn’t be wrong. Now that I’ve finished it, I think there must be a secret second version of it, because I hated this book and for the life of me can’t see what people liked about it.

I have read a lot of glowing reviews of All the Bright Places by Jennifer Niven, so I read it without even glancing at the blurb, figuring that that many people couldn’t be wrong. Now that I’ve finished it, I think there must be a secret second version of it, because I hated this book and for the life of me can’t see what people liked about it.

V.E. Schwab is a relatively popular fantasy writer. I’ve been encouraged to read her

V.E. Schwab is a relatively popular fantasy writer. I’ve been encouraged to read her

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne may be the most profoundly disappointing book I’ve ever read, and I went into it expecting not to like it. I am not a huge math or science person, and I don’t usually read a lot of science fiction so I knew it wasn’t the kind of book I’m naturally attracted to. I usually appreciate classics, though. I can generally see the merit even in the ones that I do not personally care for. I actually think that this book was subpar, though. I’m pretty sure the only reason it’s a classic is because Verne was ahead of the power curve with his descriptions of the mighty submarine. That being said, I was bored senseless. I expected a scifi story. What I got was a poorly disguised textbook about sealife classification, with about twenty pages of hunting and revenge tossed in for good measure. It wasn’t what I’d signed up for.

Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne may be the most profoundly disappointing book I’ve ever read, and I went into it expecting not to like it. I am not a huge math or science person, and I don’t usually read a lot of science fiction so I knew it wasn’t the kind of book I’m naturally attracted to. I usually appreciate classics, though. I can generally see the merit even in the ones that I do not personally care for. I actually think that this book was subpar, though. I’m pretty sure the only reason it’s a classic is because Verne was ahead of the power curve with his descriptions of the mighty submarine. That being said, I was bored senseless. I expected a scifi story. What I got was a poorly disguised textbook about sealife classification, with about twenty pages of hunting and revenge tossed in for good measure. It wasn’t what I’d signed up for. Arronax, the narrator, is some kind of marine biology writer. He never seems to fully grasp that he has been imprisoned. At least, he doesn’t care. As soon as he learns that Captain Nemo carries his book, he is totally won over. He is completely enamored by the Nautilus and by Captain Nemo, and when he is not questioning the captain unceasingly about how much steel it took to build the submarine or about old shipwrecks, he is schooling Conseil—who, aside from the six or so sentences in which he interacts with Ned and is actually kind of fun, exists just to wait on Arronax hand and foot and give him someone to lecture to—about migration patterns and mollusks and seal ears. Or something like that. In all honestly, at a certain point it just started to go in one ear and out the other. If I wanted to read about fish genus and species, I wouldn’t have looked in the fiction section of the library. This was like reading Moby Dick all over again, except that Moby Dick at least had good writing in between whale facts, and did not often resort to explaining that things defied description.

Arronax, the narrator, is some kind of marine biology writer. He never seems to fully grasp that he has been imprisoned. At least, he doesn’t care. As soon as he learns that Captain Nemo carries his book, he is totally won over. He is completely enamored by the Nautilus and by Captain Nemo, and when he is not questioning the captain unceasingly about how much steel it took to build the submarine or about old shipwrecks, he is schooling Conseil—who, aside from the six or so sentences in which he interacts with Ned and is actually kind of fun, exists just to wait on Arronax hand and foot and give him someone to lecture to—about migration patterns and mollusks and seal ears. Or something like that. In all honestly, at a certain point it just started to go in one ear and out the other. If I wanted to read about fish genus and species, I wouldn’t have looked in the fiction section of the library. This was like reading Moby Dick all over again, except that Moby Dick at least had good writing in between whale facts, and did not often resort to explaining that things defied description.