I’m going to be honest: I hated Good Night, Irene by Luis Alberto Urrea. If you want to read a positive or balanced review of it, you’ll have to find that elsewhere.

What’s it about?

Based on the experiences of the author’s mother’s real service as a ‘Donut Dolly’ during World War II, Good Night, Irene follows two women who leave home to join a little-known unit of the Red Cross. Tasked with raising morale in the troops, Irene and Dorothy drive their clubmobile Rapid City from the front lines to the officers clubs to smile and flirt with the men while serving donuts and coffee.

Why didn’t I like it?

Long story short, it’s boring and doesn’t have much of a plot.

I’m not typically a tough reviewer. I’m not stingy with four- and five-star reviews, and I always feel genuinely bad when I give something a low rating, particularly when a lot of people seem to love it. Did I miss something? At least some of my complaints are matters of taste. Historical fiction is absolutely not one of my go-to genres, and I’ve read enough WWII fiction in the last few months that I’m fairly over it. That being said, I do think that most of my critiques are legitimate and that I’m not being overly, overly mean.

Or maybe I am. Very close to the start of the novel, Irene plays a game of Solitaire and there’s some narration about the joker cards. The game of Solitaire does not use jokers. I’m usually the last person on earth to catch that sort of error, and that near immediate mistake didn’t exactly prime me to be optimistic (or charitable).

I don’t want to be unrepentantly negative, so I will say this: Urrea dedicated this novel to his mother Phyllis, who was a real-life Donut Dolly. Phyllis and her real-life clubmobile companions—including Jill, whom Urrea interviewed extensively for this project—make repeated cameos. This is very cute, and in these moments I could feel the love and respect Urrea has for her.

That doesn’t make up for the book’s many, many other flaws, though. First and foremost, as I said above, is how boring it is. I read this for book club, and while I was the only one who hated the book, I was not the only one who found it painfully slow, particularly at the beginning. Most of the others in the group felt that it picked up about halfway/two-thirds of the way through; for me it absolutely did not, but even so… the halfway point is far, far too late for the book to draw attention. I famously refuse to DNF books, but I was sorely tempted. If I’m falling asleep every few pages, don’t care about there characters, and have found no plot to speak of, what exactly am I reading to the end for? I only finished for book club, but it took me so long to get through it that I truly thought this was going to be literally the first time in my life that I didn’t finish a book club pick. I did, but barely. There is nothing propulsive about Good Night, Irene, no ‘what happens next?’ The few questions I did have never got addressed, and I wasn’t alone in feeling that the book simply lacks plot. It reads more as a collection of disconnected scenes from the war than as a cohesive narrative.

I truly think that this would have been better if Urrea hadn’t written a novel and had instead helped Jill shape her memories into a collection of essays. True stories, especially if written as a collection of anecdotes, don’t all have to build on each other the same way a novel does. In its current form, Good Night, Irene has a lot of scenes that don’t serve any clear purpose. Why, for instance, do Dorothy and Irene choose to put on cringey fake French accents for an afternoon? Generously I could say they’re trying to break the monotony or that the pressure of the war is breaking them, but I’m not truly convinced there’s evidence in the text to support it. Lots of scenes seem constructed to carry a single joke, most of which weren’t actually funny to me.

It doesn’t help that I couldn’t care less about either of the women. Some of my book club companions did like them, but for my money they’re both just empty stereotypes. Irene is a girly girl and Dorothy is a tomboy. Irene had a physically abusive fiancé and Dorothy’s brother died in the war, which is what drove them to serve. Beyond that, there’s very little to them. Worse, they very much give off men-writing-women energy. Physical descriptions are squeezed in early, at very weird times, and neither woman is at all bothered by the gross behavior they receive at the hands of the GIs.

Did Urrea not realize that even the most patriotic woman might occasionally, at least once, tire of the pawing and the flirting and the pet names? Every once in a while one of them will say “don’t call me Dolly” but it’s played like an inside joke (and the girls don’t seem to have any problem being called “doll”).

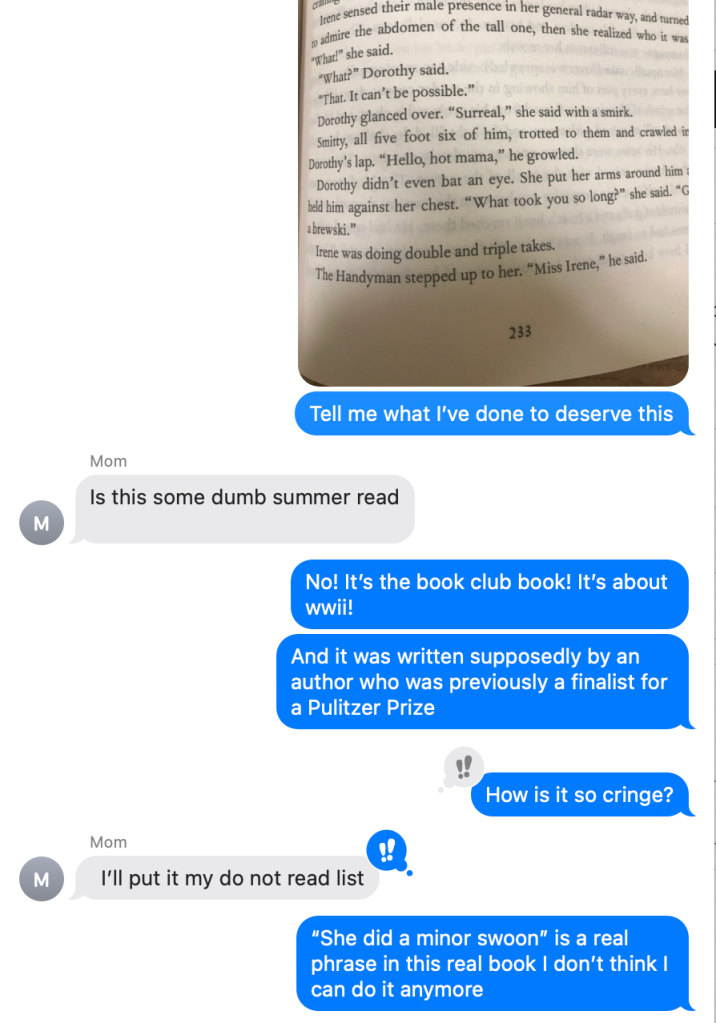

There are even moments that sound less like they were written by a human man and more like they were written by an alien educated by a man who had never met a woman before: in one scene Irene “sensed their male presence in her general radar way, and turned to admire the abdomen of the tall one” and a few sentences later Dorothy’s boyfriend “trotted to them and crawled in Dorothy’s lap. ‘Hello, hot mama,’ he growled.” I cringed very hard. In fact, I texted my mom in I’m about to quit this book despair.

Luis Alberto Urrea is a bestselling author who has won writing awards! How? He wrote the phrase “She did a minor swoon.” How am I supposed to take any of it seriously?

Even if I hadn’t seen the name on the cover of this book, there is no universe in which I could believe Good Night, Irene was written by a woman. It’s maybe not the overexaggeratedly sexed-up writing that is so maligned online, but there is something distinctly masculine about the lack of understanding about how women occupy the world, not just in the minor moments (Urrea apparently thinks that merely brushing curly hair can make it straight) but in the major ones as well. You’re telling me that Irene was repeatedly beaten by her fiancé and it’s just the inciting incident? After Irene joins the Red Cross her past abuse is never brought up again except in passing to explain why she’s there. Aside from prompting her to leave, being beaten evidently did not change Irene at all. Neither she nor Dorothy ever feels any discomfort about being constantly surrounded by armed men who haven’t seen a woman in weeks or months and who they are being asked to flirt with constantly. I’m sorry, but that would be terrifying. They receive letters that say things like I saw you for one minute six months ago and still fantasize about you or you probably don’t remember me but you gave me a donut once and I’d like to marry you after the war and they’re charmed by it. There’s not even a passing thought about this. Irene and Dorothy walk through the world—and the war—with a confidence that they’ll be untouched that is absolutely incomprehensible.

That goes double for the actual war stuff. The stated purpose of this book is to bring awareness to this under-appreciated and little-known group of war heroes, but in actuality I don’t think the Donut Dollies come across as particularly heroic here. In theory, I understand how their presence would boost morale, but Good Night, Irene makes them come across as frivolous and pampered. We’re told that they go to the front lines, but the one time they actually do experience the horrors of war upfront they’re sent overseas for an all-expenses paid beach vacation (and their boyfriends are free to just drop by). We’re told they’re sent to boost morale for the suffering GIs, but after seeing the GIs being released from a concentration camp, Patton himself apologizes to them and says he never should have sent them to see those men. When their clubmobile is shot, Irene and Dorothy’s instinctive first response is not to be afraid. It’s to be offended. They pretty much feel that they’re invincible, and why not? They’re immediately promoted to officers so that they’re treated more nicely. They apparently have an inexhaustible source of coffee and donuts, and seem to get the red carpet rolled out at every hotel stop. You wouldn’t know there was a such thing as food shortages or rationing to read this book, because the women at least are always being treated to expensive alcohol.

It just feels disingenuous to say you’re writing about women’s heroism in war and then to actually write about how the women got to go on sexy vacations, get pampered with gifts of chocolate and champagne, and prove their heroism by (spoiler) adopting a baby.

It’s not a sexist book, but it certainly doesn’t feel nearly as empowering as I expected it to, or as I assume Urrea meant it to. And just don’t get me started on the cheesy death fakeouts or the fact that the love interest is unironically called “The Handyman.”

What’s the verdict?

If you liked this book, more power to you. I barely made it through. I literally fell asleep on it more than one time (and not reading late at night; I didn’t do that with this book, because I’d rather just go to sleep intentionally) and truly thought it was going going to break my decade-long no-DNFs streak. Generally speaking, I think books should have plots, and if they don’t they definitely need to have at least one compelling character with some sort of development. Good Night, Irene does not. The best I can say about it is that I now know about the Donut Dollies, which I didn’t before, and Urrea dedicated this to his mother and her WWII heroism and that’s cute. Beyond that… Good Night, Irene is—at least for me—absolutely without anything to recommend it.

What’s next?

As far as WWII fiction goes, I highly recommend The Book Thief by Markus Zusak and The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Borrows. The Nightingale by Kristin Hannah and All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr are also good. It’s not fiction, but The Monuments Men by Robert Edsel and Bret Witter may also be a good choice. I haven’t read it, but one of my fellow book clubbers enthusiastically recommended it.

For historical fiction with compelling female characters, try The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett, Last Night at the Telegraph Club by Malinda Lo, A Clash of Steel by CB Lee, Hour of the Witch by Chris Bohjalian, The Other Boleyn Girl by Philippa Gregory, The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid, Kindred by Octavia Butler, Miss Benson’s Beetle by Rachel Joyce, or Burn by Patrick Ness. You’ll notice that not all those writers are women. Sure, women have a leg-up writing female characters, but that doesn’t mean no one else can do it well. Luis Alberto Urrea just didn’t with Good Night, Irene.

And finally a recommendation that has nothing to do specifically with Good Night, Irene but which deserves a shout-out anyway: The Scarlet Pimpernel by Baroness Orzcy, published in 1903, is often considered a predecessor to the masked superhero stories we know so well nowadays. It takes place during the Reign of Terror and tells the story of an enigmatic hero smuggling French aristocrats to safety, the agent determined to stop him, and a woman caught in the middle with an impossible choice in front of her. It’s wonderful, and doesn’t get read enough. If schools taught The Scarlet Pimpernel, more kids would grow up loving classic literature.

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows is one of my mom’s favorites, and since I read it long enough ago that I have absolutely no memory of it, I figured I would give it another shot. Since the movie recently came out, it seemed like a good time for it.

The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society by Mary Ann Shaffer and Annie Barrows is one of my mom’s favorites, and since I read it long enough ago that I have absolutely no memory of it, I figured I would give it another shot. Since the movie recently came out, it seemed like a good time for it.

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak is legitimately one of the best books I’ve ever read. If you’d rather read a glowing, non-spoilery review, go

The Book Thief by Markus Zusak is legitimately one of the best books I’ve ever read. If you’d rather read a glowing, non-spoilery review, go  Discuss in more detail Death’s direct address to the audience and its personal responses to the people in Liesel’s story. Did you find that your emotional responses tended to match Death’s? How did the constant presence of death prepare you for the mass carnage at the end of the novel? Were you prepared? Did Death’s spoiling of the final scenes ruin the surprise or build your anticipation? Why do you think Zusak chose to reveal the events of his climax so far in advance (ie. The first commentary on Rudy’s death comes on page 241; he does not die until page 531)? Why do you think that Death chose to focus specifically on Rudy’s death in the pages leading up to the bombing, rather than Hans’ or Rosa’s? Did knowing Rudy would die make you more confident about Hans and Rosa’s survival? Why do you think Death offered so many scenarios that might have changed certain’ outcomes (ie. pg. 411: “If he’d intervened it might have changed everything. […] And just maybe, [Rudy] would have lived.”).

Discuss in more detail Death’s direct address to the audience and its personal responses to the people in Liesel’s story. Did you find that your emotional responses tended to match Death’s? How did the constant presence of death prepare you for the mass carnage at the end of the novel? Were you prepared? Did Death’s spoiling of the final scenes ruin the surprise or build your anticipation? Why do you think Zusak chose to reveal the events of his climax so far in advance (ie. The first commentary on Rudy’s death comes on page 241; he does not die until page 531)? Why do you think that Death chose to focus specifically on Rudy’s death in the pages leading up to the bombing, rather than Hans’ or Rosa’s? Did knowing Rudy would die make you more confident about Hans and Rosa’s survival? Why do you think Death offered so many scenarios that might have changed certain’ outcomes (ie. pg. 411: “If he’d intervened it might have changed everything. […] And just maybe, [Rudy] would have lived.”).

Discuss Rudy Steiner as a character. What is his relationship with Liesel? How did they become friends? Discuss his growth from a young thief to a giver of bread: “How things had changed, from fruit stealer to bread giver. His blond hair, although darkening, was like a candle. She heard his stomach growl—and he was giving people bread” (440). Discuss the romantic undertone to Rudy and Liesel’s mostly innocent relationship; when did Rudy begin to see Liesel that way? When did Liesel begin to see Rudy that way? Consider the kiss that Rudy is always asking for but which Liesel does not give him until after his death. Why do you think Zusak chose Rudy’s death to emphasize? Discuss Death’s regret over Rudy (pg. 241: “He didn’t deserve to die the way he did”) and his urging Liesel to kiss him while she had the chance (pg. 454: “Kiss him, Liesel, kiss him”). At the end, Death says of Rudy, “He does something to me, that boy. Every time. It’s his only detriment. He steps on my heart. He makes me cry” (531). Why does Rudy affect Death in ways that others don’t? Also be sure to discuss the Jesse Owens Incident, Rudy’s extraordinary intelligence and athleticism that caught the attention of the Nazi higher-ups, and his childish insolence and feud with his Hitler Youth teacher.

Discuss Rudy Steiner as a character. What is his relationship with Liesel? How did they become friends? Discuss his growth from a young thief to a giver of bread: “How things had changed, from fruit stealer to bread giver. His blond hair, although darkening, was like a candle. She heard his stomach growl—and he was giving people bread” (440). Discuss the romantic undertone to Rudy and Liesel’s mostly innocent relationship; when did Rudy begin to see Liesel that way? When did Liesel begin to see Rudy that way? Consider the kiss that Rudy is always asking for but which Liesel does not give him until after his death. Why do you think Zusak chose Rudy’s death to emphasize? Discuss Death’s regret over Rudy (pg. 241: “He didn’t deserve to die the way he did”) and his urging Liesel to kiss him while she had the chance (pg. 454: “Kiss him, Liesel, kiss him”). At the end, Death says of Rudy, “He does something to me, that boy. Every time. It’s his only detriment. He steps on my heart. He makes me cry” (531). Why does Rudy affect Death in ways that others don’t? Also be sure to discuss the Jesse Owens Incident, Rudy’s extraordinary intelligence and athleticism that caught the attention of the Nazi higher-ups, and his childish insolence and feud with his Hitler Youth teacher. Discuss the novel’s depiction of WWII and Nazi Germany. Why do you think that Zusak decided to center his novel around a young German girl who by and large is accepted by the higher powers, rather than a traditional victim of the Nazi violence? Jews (pg. 161: “anything was better than being a Jew”), Communists (Liesel’s father was taken away for being one), and black people (pg. 56: “Talk that [Jesse Owens] was subhuman because he was black and Hitler’s refusal to shake his hand were touted around the world”) are singled out for discrimination, but Liesel is none of these things. Despite this, she is still a victim of Hitler and WWII. Discuss Liesel’s upbringing; what is normal for her? Is it jarring for you to read about a protagonist whose friends and neighbors are members of the Nazi Party, who is a member of Hitler Youth, and who Heil Hitler!s on the regular? Why or why not?

Discuss the novel’s depiction of WWII and Nazi Germany. Why do you think that Zusak decided to center his novel around a young German girl who by and large is accepted by the higher powers, rather than a traditional victim of the Nazi violence? Jews (pg. 161: “anything was better than being a Jew”), Communists (Liesel’s father was taken away for being one), and black people (pg. 56: “Talk that [Jesse Owens] was subhuman because he was black and Hitler’s refusal to shake his hand were touted around the world”) are singled out for discrimination, but Liesel is none of these things. Despite this, she is still a victim of Hitler and WWII. Discuss Liesel’s upbringing; what is normal for her? Is it jarring for you to read about a protagonist whose friends and neighbors are members of the Nazi Party, who is a member of Hitler Youth, and who Heil Hitler!s on the regular? Why or why not? Discuss the role of fate and chance in the novel. Hans cheated death twice; the second time is entirely coincidental: a man dislikes Hans so he kicks him out of his usual seat and ends up dying because of it. Death says, “It kills me sometimes, how people die” (464). Sometimes, events that seem like blessings (Rudy not being sent away, Hans returning home from war) eventually prove to be curses. Death says, “You save someone. You kill them. How was he supposed to know?” (547). It is impossible to tell what actions will have what responses. Discuss.

Discuss the role of fate and chance in the novel. Hans cheated death twice; the second time is entirely coincidental: a man dislikes Hans so he kicks him out of his usual seat and ends up dying because of it. Death says, “It kills me sometimes, how people die” (464). Sometimes, events that seem like blessings (Rudy not being sent away, Hans returning home from war) eventually prove to be curses. Death says, “You save someone. You kill them. How was he supposed to know?” (547). It is impossible to tell what actions will have what responses. Discuss.